IFF technology aims for a safer battlefield

StoryMay 06, 2021

By Dawn M.K. Zoldi

Enemy suicide drones, spy drones, and drones that deliver death and destruction increasingly complicate the modern battlefield. The advent of unmanned aircraft system (UAS) technology has enabled non-state actors to harness airpower in a way previously reserved for the large military forces of nation-states. For as little as $650 for an off-the-shelf UAS, an enemy can eviscerate a parked F-22 worth $344 million. This low-cost/high-impact threat vector fundamentally alters force protection and installation defense requirements for the U.S. and its allies.

As most military conflicts involve joint, coalition, and interagency players, having one technology to help all friendly forces identify the full spectrum of hostile drone platforms is a game changer. The advent of multiplatform unmanned aerial system (UAS) identification technology will enable U.S. service members and coalition partners to more readily determine if an inbound UAS is friend or foe, allowing them to react before it’s too late.

The enemy UAS challenge

UASs are versatile. That’s why U.S. and partner forces use them. They can overfly barriers, observe the positions of assets and operations, and accurately deliver lethal and nonlethal payloads from afar to damage, disable, or destroy critical capabilities and forces. UASs themselves can be used as guided missiles. That’s also why the enemy now regularly uses them.

However, the use of UASs in warfare is not new, but simply now more common. Although aircraft without pilots technically date back to 1783, it was not until the 1990s that the weaponized Predator drone became a staple of modern warfare. It was around that same time that criminals and insurgents started incorporating small drones into their own plans. As early as 1994, the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo conducted unsuccessful dry runs to release sarin, a nerve agent, using aerial spray systems attached to remote-controlled helicopters. Over the years, the list of nefarious actors and their creative uses of drones continued to grow.

Fast forward in time. In the past few years, UASs have now become the weapon of choice for insurgents in Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. In 2017, ISIS flew more than 300 UAS missions in one month during the battle for Mosul, where troops observed them dropping hand grenades. Two years later in Yemen, during a parade near Aden, a weaponized UAS exploded atop several senior Saudi-backed Yemeni officers, killing at least six.

Late in 2020, the Taliban appears to have carried out a UAS attack that killed at least four security officers in northern Afghanistan. In February 2021, Iranian-backed Houthi rebels used a Qasef-1 to target civilian aircraft at Saudi Arabia’s Abha airport, one of twelve recent UAS attacks on the country.

Now add civilian UAS to the equation. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) performing humanitarian missions and locals flying their hobby UASs further complicate the airspace picture.

Due to the proliferation of UAS in combat theaters, commanders today require an accurate means to identify them in order to fulfill their obligation to protect their forces while defeating the enemy.

The rules of engagement

The law of armed conflict (LOAC) is a specialized subset of international humanitarian law and applies to armed hostilities. The LOAC governs behavior on the battlefield and is further ensconced in rules of engagement (ROE). Joint Publication 1-02 promulgated by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) defines the ROE as: “… directives issued by competent military authority that delineate the circumstances and limitations under which United States forces will initiate and/or continue combat engagement with other forces encountered.”

For U.S. forces, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) Instruction 3121.01B, Standing Rules of Engagement for U.S. Forces (SROE), is the general foundation upon which commanders base theater-specific or other tailored ROE across the range of military operations. For multinational forces, reasonable efforts will be made to create common ROE. Regardless, U.S. national policy preserves a commander’s inherent authority and obligation to use all necessary means available and to take appropriate action in self-defense of the commander’s unit and other U.S. forces in the vicinity. This includes the concepts of self-defense, national defense, collective defense, and unit defense.

Each type of defensive concept contains nuances. Hostile acts are obvious, such as an outright attack, whereas hostile intent, or “the threat of imminent use of force,” can sometimes prove more difficult. For example, how exactly does one determine the intent of an UAS?

The UAS operator’s identity, capability and intentions will likely remain elusive. On the other hand, “If it ain’t ours, it must be theirs.” And if it’s theirs, it should be fair game, especially if the worst-case scenario does not involve taking a life. Until recently, knowing whether or not an UAS was “ours” – especially for groups 2 and 3 drones (anywhere from 21 to 1,320 pounds) – remained somewhat of a mystery, which makes obvious the need for interoperability requirements and transponders.

IFF functionality

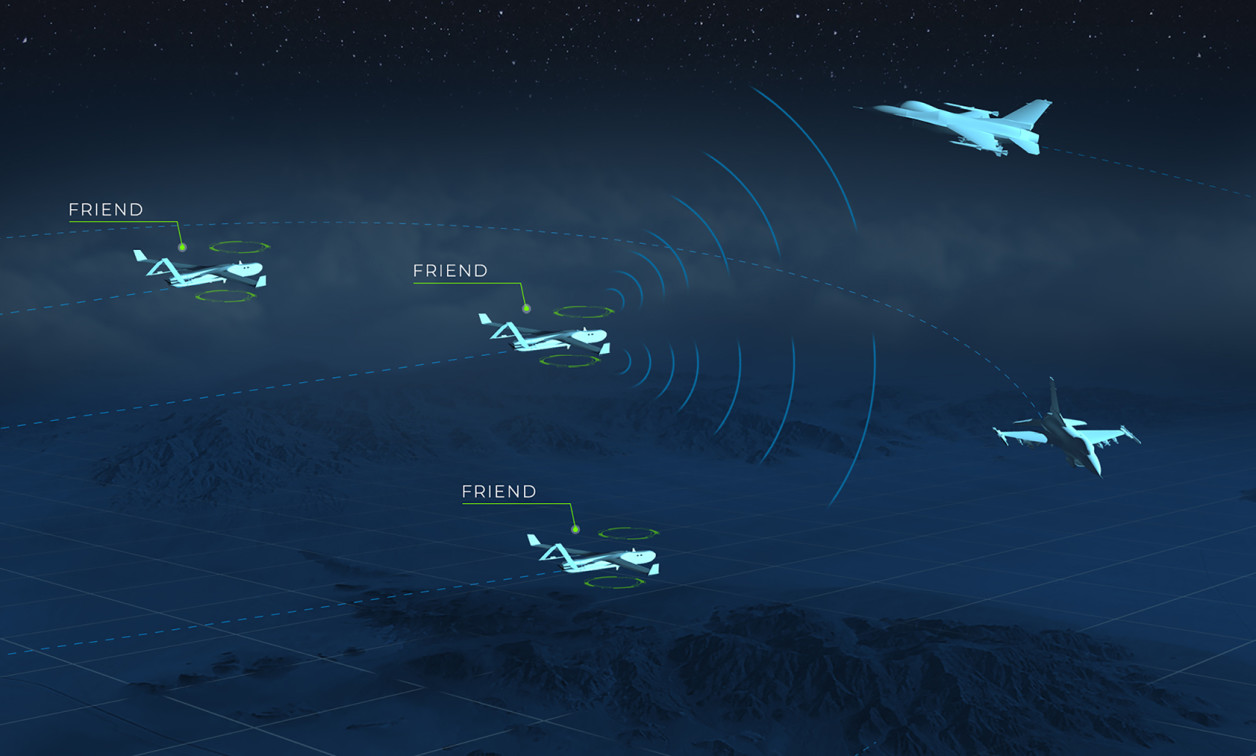

For years, to determine which aircraft is part of the home team, and thereby reduce fratricides and successful enemy attacks, militaries worldwide have been using Identify Friend or Foe (IFF) systems for command-and-control on aircraft. These military RF-based identification systems positively distinguish friendly aircraft from those of the enemy using spread-spectrum transmissions with secure data encryption. An IFF system consists of an airborne transponder with a ground or airborne interrogator. The interrogator sends encrypted, coded information requests to the aircraft, and the transponder encodes identification and position information into the response. (Figure 1.)

“A decade ago, advanced drone technology in areas of conflict was generally limited to the U.S. and her allies. Today, even the most unsophisticated hostile forces have access to very similar technology,” says Sagetech Avionics CEO Tom Furey. “Now that IFF technology has been miniaturized, we can finally distinguish between friendly and hostile UAS to take appropriate action to protect our troops and infrastructure.”

[Figure 1 | An airborne transponder (top, mounted on a UAS) replies to encrypted information requests from an interrogator to ascertain identification and position of unknown aircraft. Sagetech graphic.]

IFF can only positively identify friendly targets, not hostile ones; however, the ability to discriminate across the full spectrum of drones can make a lifesaving difference in protecting the lives of deployed troops and avoiding tragic fratricide events. Further, current U.S. forces’ operating procedures often restrict crucial manned aircraft flights when unmanned aircraft are operating in the vicinity, since not all aircraft can be positively identified. When coalition forces are operating collectively, the problem escalates exponentially. In these situations, small IFF solves these problems for all allied and NATO forces.

This situation is exactly why standard agreements and processes exist for aircraft identification among multinational forces – to rule out compliant “blue” or friendly forces as potential threats. NATO publishes STANAGs, recorded agreements among several or all NATO member states (ratified at the authorized national level) to implement a standard. In STANAG 4193, NATO enacted a requirement that all military aircraft update to IFF Mode 5 by July 2020. Mode 5 IFF requires stronger encryption, different transmitter response prioritization, and GPS information about target aircraft locations than Mode 4, which had been used since the 1970s through its retirement in July 2020.

On the U.S. side, the DoD AIMS (Air Traffic Control Radar Beacon System, Identification Friend or Foe, Mark XII/Mark XIIA/XIIB, Systems) Office requires that IFF systems comply with the Mark XIIB standard as specified in AIMS 17-1000, which replaced AIMS 03-1000 (Mark XIIA). The AIMS IFF certification process is complicated, interagency, and lengthy, requiring thousands of hours of testing and evaluation prior to approval.

The new IFF standard, Mark XIIB, requires the following functionalities:

- Military Modes 1, 2, 3/C, and 5: These are the transponder interrogation modes, standard formats of pulsed sequences from an interrogating SSR or similar Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) system; Modes 1 to 5 are for military use

- Civil Modes A, C, and S functionality: These are for civilian use

- ADS-B Out: Enables equipped aircraft and ground vehicles to broadcast their identification, position, altitude, and velocity to other aircraft and air-traffic control

- Mode 5 response prioritization

- Antenna diversity for full aircraft visibility

- Incorporation of internal crypto, or compatibility with an external crypto computer such as the KIV-77 or KIV-78

- Full transmit power per AIMS 17-1000

- Satisfy the robust environmental standards of MIL-STD-461 and MIL-STD-8

Combined, these elements enhance robust systems to bolster situational awareness.

First to cert

On February 5, 2021, the DoD AIMS Program Office issued the world’s first 17-1000 Mark XIIB certification to Sagetech for its MX12B micro Mode 5 IFF transponder. The small military-grade transponder weighs only 190 g, or slightly more than one-third of a pound. The MX12B also includes extra features, such as ADS-B In, that tracks as many as 400 cooperative targets simultaneously and displays them for the remote pilot in the command-and-control graphical user interface. For the anticipated future changes to the MKXIIB standard, the unit is upgradeable to Mode 5 Level 2-B In and Out. (Figure 2.)

[Figure 2 | The MX12B micro Mode 5 IFF transponder from Sagetech weighs just 190 g. Sagetech photo.]

Dawn M.K. Zoldi (Colonel, USAF, Retired) is a licensed attorney with 28 years of combined active-duty military and federal civil service to the Department of the Air Force. She is an internationally recognized expert on unmanned aircraft system law and policy, the Law-Tech Connect columnist for Inside Unmanned Systems magazine, a recipient of the Woman to Watch in UAS (Leadership) Award 2019, and the CEO of P3 Tech Consulting LLC. For more information, visit her website at: https://www.p3techconsulting.com.

Sagetech https://sagetech.com/

Featured Companies

Sagetech Corporation

White Salmon, WA 98672